|

|

| J Rhinol > Volume 30(1); 2023 |

|

Abstract

Background and Objectives

The purpose of this study was to conduct a meta-analysis of the effects of intraoperative pharyngeal packing on postoperative nausea, vomiting, and sore throat in nasal surgery patients.

Methods

Databases were searched from inception to December 2022. Randomized controlled trials comparing saline-soaked pharyngeal packing (packing group) with no packing (control group) during intubation in patients undergoing nasal surgery were included. The primary outcomes of interest were the incidence of postoperative nausea, vomiting, and sore throat at 24 hours.

Results

Eleven studies, including a total of 931 patients, were included. There was no significant difference between the two groups in the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting and severity scores at 2, 6, and 24 hours postoperatively. The incidence of throat pain was higher in the packing group than in the control group immediately after surgery and at 24 hours postoperatively. However, no significant difference was observed between the two groups in the incidence of sore throat at 6 and 12 hours postoperatively.

Nausea and vomiting are frequent complications of nasal surgery. There are several causes of nausea and vomiting, including patient factors, anesthetics, and opiate analgesics, but ingested blood is also known to be a major cause. Cuffed endotracheal tubes are not thought to be completely effective in protecting against the aspiration of hypopharyngeal blood [1]. Surgery in the nasal cavity and sinuses can cause severe bleeding because these are areas with abundant blood vessels [2]. Therefore, pharyngeal packing is often performed by clinicians during nasal surgery to minimize blood entry into the esophagus and thus reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting [3].

However, pharyngeal packing can also cause complications related to the act itself, such as sore throat after surgery. Sore throat is an adverse effect that occurs due to compression and irritation of the packing on the pharyngeal mucosa [4]. The incidence of throat pain after nasal surgery varies from 14.4% to 50%, and has been reported in up to 60% of patients who receive pharyngeal packing [5]. Therefore, debate continues regarding whether it is beneficial to perform pharyngeal packing during nasal surgery. In fact, some studies have reported that pharyngeal packing had no effect on reducing the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting, but rather was associated with an increased incidence of sore throat. Therefore, the purpose of this meta-analysis was to evaluate the efficacy of using pharyngeal packing to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting compared to patients who did not use pharyngeal packing, and to determine whether it also affects the occurrence of throat pain.

Studies published before December 2022 in PubMed Central, MEDLINE, Scopus, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials with the keywords “pharyngeal packing,” “postoperative nausea,” “vomiting,” “throat pain,” “sore throat,” and “nasal surgery” (including functional endoscopic sinus surgery, septoplasty, septal surgery, septorhinoplasty, turbinectomy, turbinoplasty, nasal polypectomy, and nasal adhesions lysis) were searched. Two reviewers independently evaluated the data extracted from the database, and articles irrelevant to the research topic were excluded based on the title and abstract. If the items selected by the two reviewers were different, the final choice regarding inclusion was made through discussion with a third reviewer. We limited inclusion to randomized controlled trials in which saline-soaked pharyngeal packing was performed on patients during nasal surgery under general anesthesia. Studies were excluded from the analysis if: 1) additional surgery was performed (e.g., middle ear surgery or pharyngeal surgery); 2) patients had a previous history of postoperative nausea and vomiting; 3) patients had underlying diseases such as systemic or malignant diseases; 4) multiple reports were based on the same test data; or 5) data necessary for the analysis were missing or incomplete, making it impossible to extract and calculate appropriate data. The overall article selection process is presented in Fig. 1.

The primary outcome was the incidence and severity of nausea and vomiting on the first day after nasal surgery under general anesthesia. The control group comprised patients who did not perform pharyngeal packing. The incidence and severity of throat pain were also assessed as secondary outcomes.

The extracted data were organized using a standardized extraction form and listed as follows: the number of patients with postoperative nausea, vomiting, and sore throat, the incidence (as a percentage), and the p-value for the comparison between the packing and control groups. Quality assessment was conducted using the Cochrane Risk of bias tool.

Meta-analysis was performed using the R Statistical Software (R-4.2.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). When the extracted data were continuous, a meta-analysis was performed using the standardized mean difference (SMD). Odds ratios (ORs) were used to analyze incidence. A funnel plot and the Egger test were conducted together to assess publication bias. We also adjusted for missing studies using the Duval and Tweedie trim-and-fill method and corrected the overall effect size for publication bias. We also performed a sensitivity analysis to estimate the impact of each individual study on the overall meta-analysis results.

Eleven studies, with 931 participants, were reviewed for eventual inclusion in this meta-analysis [1-11]. The study characteristics and quality assessment are presented in Table 1.

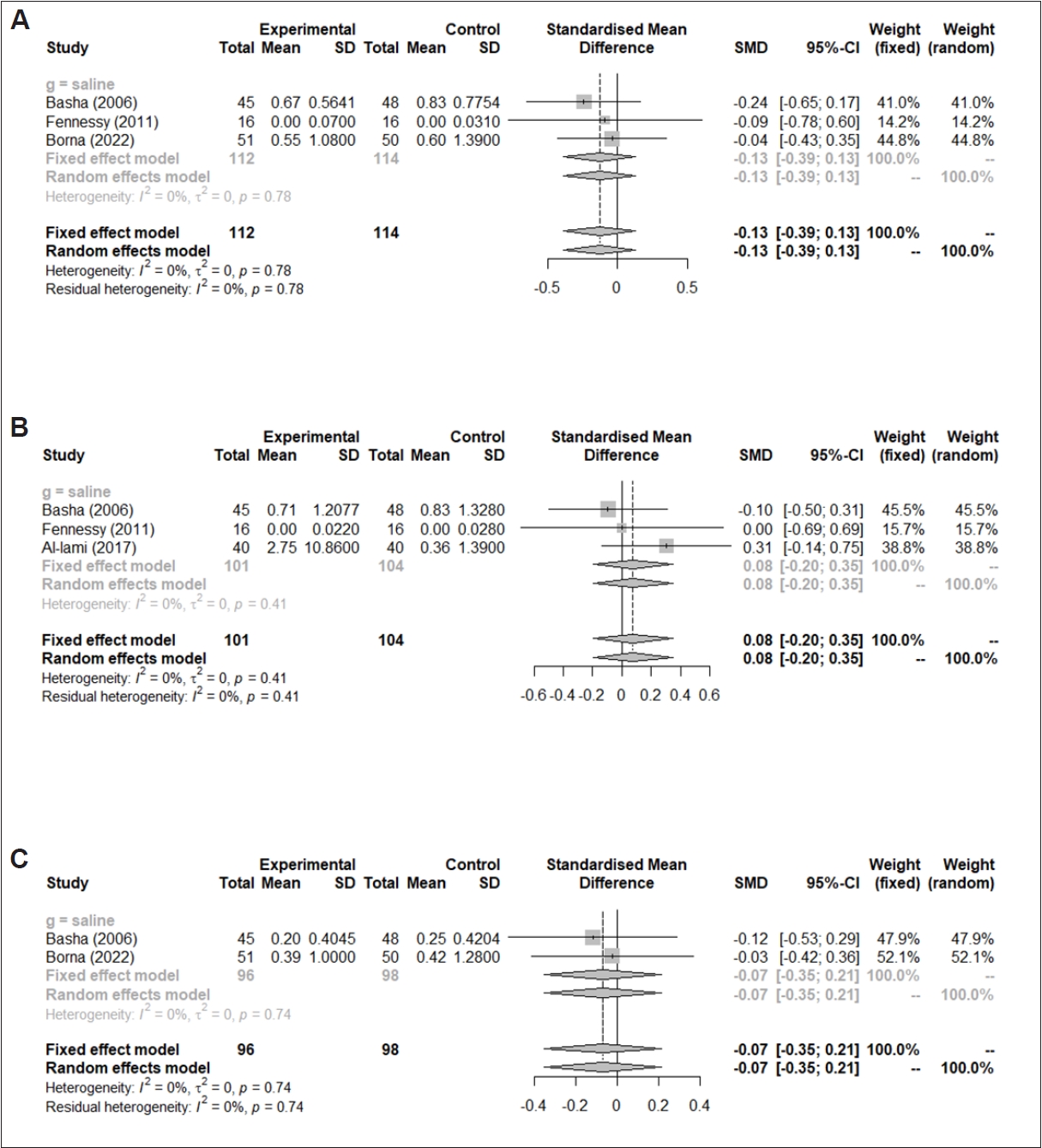

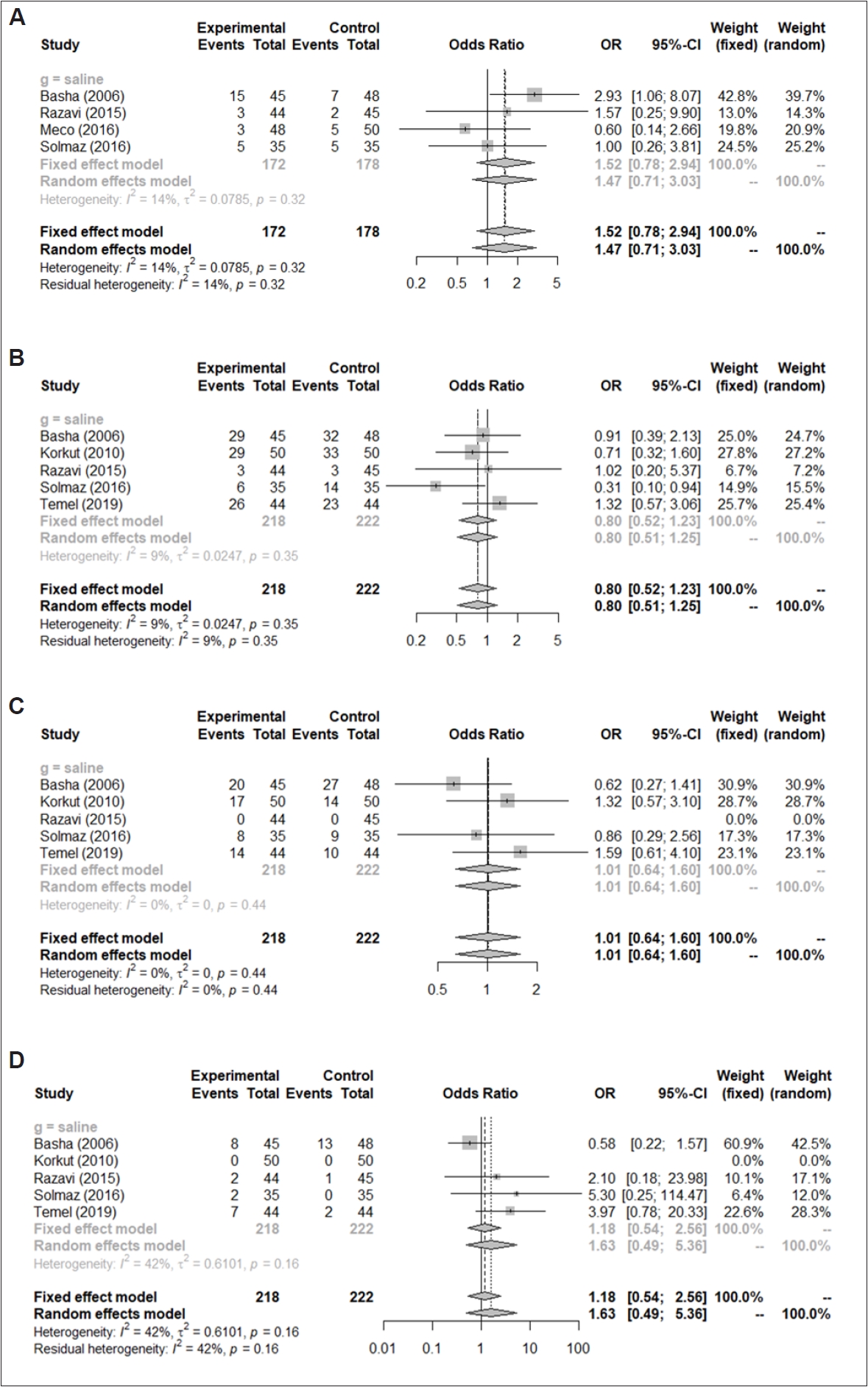

No significant differences in postoperative nausea and vomiting severity scores were found at postoperative 2 hours (SMD=-0.13, 95% CI: -0.39–0.13, I2=0%), 6 hours (SMD=0.08, 95% CI, -0.20–0.35, I2=0%), and 24 hours (SMD=-0.07, 95% CI: -0.35–0.21, I2=0%) between patients who received pharyngeal packing and patients who did not receive packing (control group) (Fig. 2). Similarly, the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting in the packing group were not significantly different from that in the control group immediately after surgery (OR=1.52, 95% CI: 0.78–2.94, I2=14%), postoperative 2 hours (OR=0.80, 95% CI: 0.52–1.23, I2=9%), 6 hours (OR=1.01, 95% CI: 0.64–1.60, I2=0%), and 24 hours (OR=1.18, 95% CI: 0.54–2.56, I2=42%) (Fig. 3). No statistically significant inter-study heterogeneity (I2 <50%) was found in these outcomes. The Duval and Tweedie trim-and-fill method and the Egger test regarding postoperative nausea and vomiting at all time points were not conducted due to an insufficient number of enrolled studies (<10).

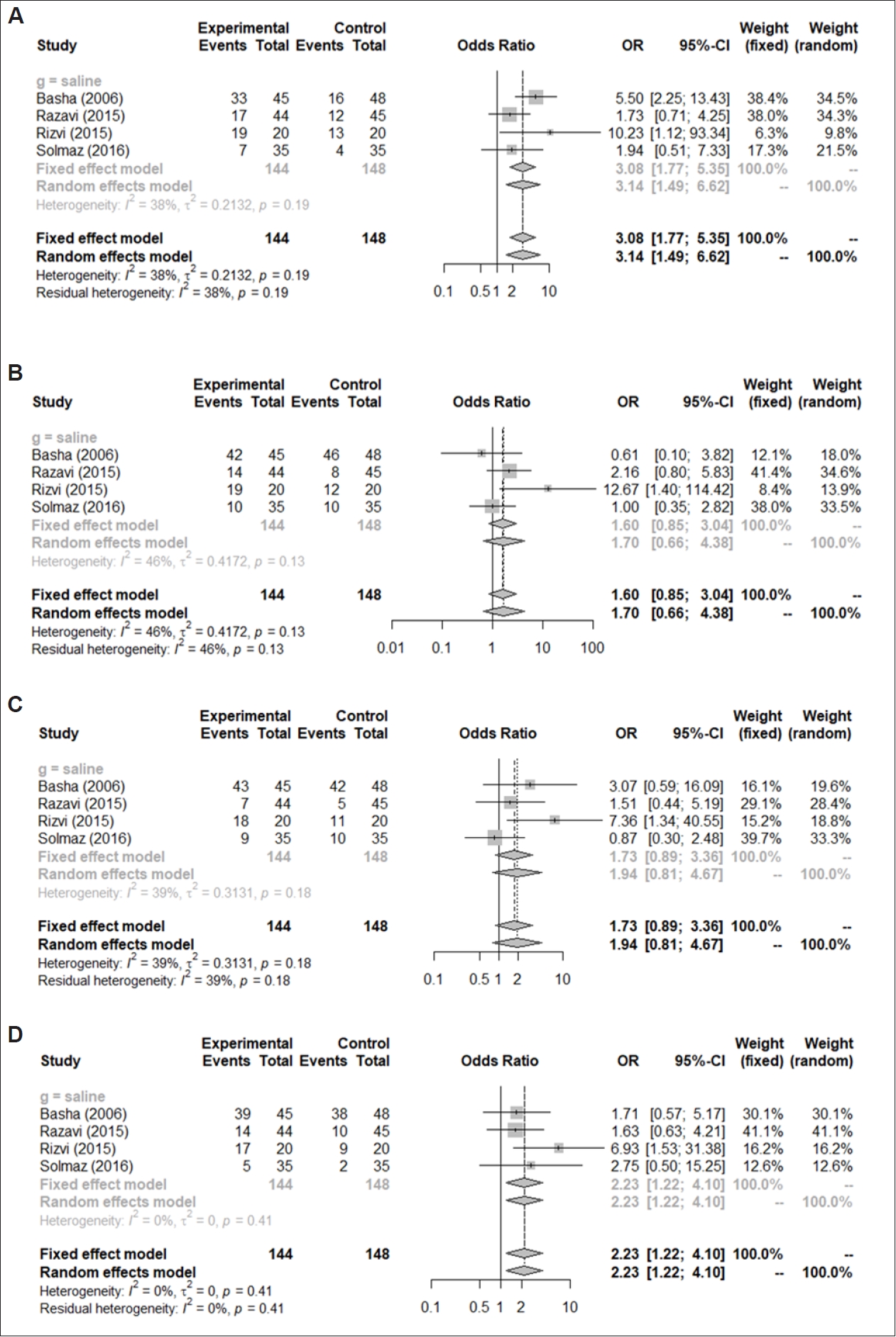

Throat pain scores at recovery status immediately after surgery (SMD=0.40, 95% CI: 0.20–0.59, I2=43%) and at postoperative 24 hours (SMD=0.33, 95% CI: 0.11–0.55, I2=0%) were significantly higher in the packing group than in the control group, except at postoperative 2 hours (SMD=0.18, 95% CI: -0.37–0.74, I2=73%) and 6 hours (SMD=-0.04, 95% CI: -0.74–0.67, I2=83%) (Fig. 4). Similarly, the incidence of throat pain immediately after surgery (OR=3.08, 95% CI: 1.77–5.35, I2=38%) and at 24 hours (OR=2.23, 95% CI: 1.22–4.10, I2=0%) were statistically significantly higher in patients who had received pharyngeal packing than in the control group (Fig. 5). In contrast, no significant differences were found in the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting between the two groups at postoperative 2 hours (OR=1.60, 95% CI: 0.85–3.04, I2=46%) and 6 hours (OR=1.73, 95% CI: 0.89–3.36, I2=39%).

No statistically significant inter-study heterogeneity was found (I2<50%) in these outcomes except for pain scores at postoperative 2 hours and 6 hours. The Duval and Tweedie trim-and-fill method and the Egger test for throat pain at alltime points were not conducted due to an insufficient number of enrolled studies (<10).

Nausea and vomiting after surgery are uncomfortable and can be caused by bleeding, dehydration, electrolyte and acidbase imbalances, and lung aspiration. In addition, nausea and vomiting also prolong the time the patient stays in the treatment room, with longer anesthesia, and discharge may be delayed. Postoperative nausea and vomiting can also induce anxiety and reduce patients’ satisfaction with nasal surgery. Therefore, routine patient management protocols should include evaluating and controlling symptoms of nausea and vomiting after nasal surgery [4].

We used detailed temporal categories in this meta-analysis to accurately reflect changes over time in the effect of pharyngeal packing on postoperative nausea and vomiting. Sore throat was also evaluated as a side effect.

The meta-analysis confirmed that postoperative nausea and vomiting symptoms showed no significant differences between groups, while sore throat in the recovery room was more frequent in the packing group than in the control group. It is known that pharyngeal packing may cause local trauma and inflammation of the pharyngeal mucosa, which may be associated with pharyngeal plexus injury and tongue swelling [1]. Trauma to the pharynx can irritate the vagus nerve nucleus in the brainstem and cause vomiting [2]. Considering this relationship, pharyngeal packing may in fact cause nausea and vomiting due to sore throat during postoperative recovery.

Although the results of the early (immediate recovery after surgery) and mid-term (2 hours after surgery) showed conflicting patterns, the total number of antiemetic administrations within 24 hours after surgery was statistically similar between the two groups. Ingested blood after surgery can induce very strong vomiting, but actual postoperative nausea and vomiting may be affected by a variety of factors, including individual patient factors, intraoperative management, and postoperative management [8]. Therefore, performing pharyngeal packing during nasal surgery can theoretically reduce blood product intake and reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting. However, other factors, such as damage to the pharyngeal mucosa and postoperative pain control, may also affect the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting. The analysis of patterns at multiple time points within 24 hours postoperatively in this study showed that inserting pharyngeal packing did not reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting, but increased throat discomfort in patients after surgery.

Our study had several limitations. The study included various surgical procedures, such as septoplasty, rhinoplasty, and endoscopic sinus surgery. The amount of bleeding and packing time may vary depending on the severity of the condition or differences in individual surgical methods. This issue may explain the high heterogeneity in the values of throat pain. Nonetheless, although several studies (either case series or case-control studies) have presented mixed results regarding the effectiveness of pharyngeal packing, only randomized controlled trials were included in this meta-analysis to improve the validity of the findings.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Do Hyun Kim and Se Hwan Hwang who are on the editorial board of the Journal of Rhinology were not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Se Hwan Hwang. Data curation: Do Hyun Kim, Se Hwan Hwang. Formal analysis: Se Hwan Hwang. Methodology: Se Hwan Hwang. Project administration: Do Hyun Kim. Supervision: Se Hwan Hwang. Validation: Do Hyun Kim. Visualization: Se Hwan Hwang. Writing—original draft: Do Hyun Kim. Writing—review & editing: Do Hyun Kim, Se Hwan Hwang.

Table 1.

Summary of studies and risk of bias assessment

| Study (year) | Sample size | Age, yr (mean, range or SD) | Sex (male-to-female ratio) | Study design | Comparison | Outcome measure analyzed | Risk of bias of randomized studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basha et al. [1] (2006) | 93 | 34 (16–81) | 69 Males and 24 females | RCT | Pharyngeal packing (saline) vs. no packing | Postoperative nausea and vomiting, throat pain | Unclear risk |

| Meco et al. [8] (2016) | 201 | 45 (11) | 111 Males and 90 females | RCT | Pharyngeal packing (saline) vs. no packing | Postoperative nausea and vomiting | Unclear risk |

| Korkut et al. [2] (2010) | 100 | 30.5 (11.95) | Not declared | RCT | Pharyngeal packing (saline) vs. no packing | Postoperative nausea and vomiting | Low risk |

| Rizvi et al. [9] (2015) | 40 | 35 (15–60) | NA | RCT | Pharyngeal packing (saline) vs. nasal packing | Throat pain | Unclear risk |

| Solmaz et al. [10] (2016) | 105 | 29 (20), 2 not declared | NA | RCT | Pharyngeal packing (saline) vs. no packing | Postoperative nausea and vomiting, throat pain | Unclear risk |

| Razavi et al. [5] (2015) | 89 | 27.18 (7.08) | 89 Males and 35 females | RCT | Pharyngeal packing (saline) vs. no packing | Postoperative nausea and vomiting, throat pain | Low risk |

| Fennessy et al. [3] (2011) | 32 | 39 (19–62) | NA | RCT | Pharyngeal packing (saline) vs. no packing | Postoperative nausea and vomiting, throat pain | Low risk |

| Karbasforushan et al. [4] (2014) | 140 | 20–40 | 61 Males and 79 females | RCT | Pharyngeal packing (saline) vs. no packing | Throat pain | Unclear risk |

| Al-Lami et al. [6] (2017) | 80 | 42 (18–72) | 57 Males and 23 females | RCT | Pharyngeal packing (saline) vs. no packing | Postoperative nausea and vomiting, throat pain | Low risk |

| Temel et al. [11] (2019) | 88 | 30.18 (8.98) | 56 Males and 32 females | RCT | Pharyngeal packing (saline) vs. no packing | Postoperative nausea and vomiting | Low risk |

| Borna et al. [7] (2022) | 101 | 35.0 (18–61) | 81 Males and 20 females | RCT | Pharyngeal packing (saline) vs. no packing | Postoperative nausea and vomiting, throat pain | Low risk |

References

1) Basha SI, McCoy E, Ullah R, Kinsella JB. The efficacy of pharyngeal packing during routine nasal surgery--a prospective randomised controlled study. Anaesthesia 2006;61(12):1161–5.

2) Korkut AY, Erkalp K, Erden V, Teker AM, Demirel A, Gedikli O, et al. Effect of pharyngeal packing during nasal surgery on postoperative nausea and vomiting. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010;143(6):831–6.

3) Fennessy BG, Mannion S, Kinsella JB, O’Sullivan P. The benefits of hypopharyngeal packing in nasal surgery: a pilot study. Ir J Med Sci 2011;180(1):181–3.

4) Karbasforushan A, Hemmatpoor B, Makhsosi BR, Mahvar T, Golfam P, Khiabani B. The effect of pharyngeal packing during nasal surgery on the incidence of post operative nausea, vomiting, and sore throat. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol 2014;26(77):219–23.

5) Razavi M, Taghavi Gilani M, Bameshki AR, Behdani R, Khadivi E, Bakhshaee M. Pharyngeal packing during rhinoplasty: advantages and disadvantages. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol 2015;27(83):423–8.

6) Al-Lami A, Amonoo-Kuofi K, Kulloo P, Lakhani R, Prakash N, Bhat N. A study evaluating the effects of throat packs during nasal surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2017;274(8):3109–14.

7) Borna R, McCleary S, Wang L, Lee A, Saadat S, Grogan T, et al. Effect of throat pack placement on the incidence of sore throat and postoperative nausea and vomiting in septorhinoplasty patients: a randomized controlled trial. Aesthet Surg J 2022;42(7):743–8.

8) Meco BC, Ozcelik M, Yildirim Guclu C, Beton S, Islamoglu Y, Turgay A, et al. Does type of pharyngeal packing during sinonasal surgery have an effect on PONV and throat pain? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016;154(4):742–7.

9) Rizvi MM, Singh RB, Rasheed MA, Sarkar A. Effects of different types of pharyngeal packing in patients undergoing nasal surgery: a comparative study. Anesth Essays Res 2015;9(2):230–7.

10) Solmaz FA, Tutal ZB, Turhan KSC, Ozatamer O, Meco C. Effects of pharyngeal tampon usage for postoperative nause, vomiting and sore throat in nasal surgery. Int J Clin Exp Med 2016;9(7):14442–7.

-

METRICS

-

- 3 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

- 1,812 View

- 35 Download

- Related articles

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print