|

|

| J Rhinol > Volume 29(2); 2022 |

|

Abstract

Various invasive fungal infections can occur in immunocompromised hosts, and an acute invasive fungal infection (AIFI) can be fatal. Because of its high mortality rate, AIFI must be quickly diagnosed and treated, such as anti-fungal agents or surgical debridement. In an immunocompromised host, nasal herpes simplex infection, usually caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV) type-1, can have various clinical manifestations, some of which can mimic AIFI. However, the management of acute viral infection differs significantly from invasive fungal infections of the nose. A fast and accurate differential diagnosis is mandatory because a delay in the disease-specific treatment of acute invasive infections can lead to mortality. This report describes two immunocompromised patients with mucosal and skin lesions around the nose. We provide clinical clues when mucosal lesions of the nasal cavity and skin lesions around the nose develop in immunocompromised hosts.

Acute invasive fungal infection (AIFI) of the nasal cavity and external nose is an infectious disease caused by fungi such as Mucor, Rhizopus, and Aspergillus. It occurs mainly when the immune response deteriorates after transplantation and can also occur in case of neutropenia led by the administration of immunosuppressants or chemotherapy, uncontrolled diabetes, autoimmune disease, etc. [1]. If the fungus invades the mucous membranes of the nasal cavity or sinuses, mucosal edema, degenerative change such as dryness or paleness, and persistent crusting can be observed in endoscopic examination. When a thrombus is formed after it further progresses to a blood vessel, it causes ulcers and necrotic lesions of the skin and mucous membranes [2].

AIFI is a rare disease but has a high mortality rate. Therefore, it is important to make sure that doctors conduct an active differential diagnosis to prevent any delay in treatment when mucosal lesions in the nasal cavity are observed in immunocompromised patients.

Intranasal herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection is mainly caused by HSV type-1 [3]. It appears as clustered blisters or ulcers in skin lesions accompanied by symptoms such as erythematous changes, and causes pain, itching, and burning. However, it can be expressed in various clinical manifestations in immunocompromised patients and is sometimes confused with cutaneous lymphoma because lymphocyte infiltration is accompanied by histopathology [4]. The authors analyzed two cases of HSV infection, not AIFI, in a biopsy for diagnosis of necrotic lesions of the nasal mucosa and skin surrounding the external nose in immunocompromised patients in order to provide clinical clues of HSV infection and examine the diagnosis and treatment of two diseases with completely different prognosis and treatment methods.

A 29-year-old male patient, who had undergone allogeneic peripheral hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for severe aplastic anemia, developed necrotic lesions on the skin of the left nasal septum and columella while receiving treatment for neutropenic fever and septic shock. Debridement was conducted at a different hospital, and fungal infection was confirmed during histological examination. He was transferred to our hospital, and antifungal drugs were administered with suspicion of having fungal infection in the liver and lungs. The patient complained of nasal obstruction due to a large amount of crusts in the left nasal cavity. There were no other nasal symptoms such as rhinorrhea or postnasal drip. He also had no previous experience of being diagnosed with or treated for rhinosinusitis. On examination, a large amount of erythematous changes and hemorrhagic crusts were found in the columella, subnasale to alar rim in the left nose, and that there were mucosal paleness and ulcerative mucosal changes accompanied by edema and pallor in the anterior septum and lateral mucous membrane of the inferior turbinate (Fig. 1A). For tissue diagnosis and treatment, debridement and biopsy were performed. There was no improvement in the intranasal lesion after the operation. A few days later, new ulcerative lesions were developed on the lip and gingiva of the left maxillary second molars (Fig. 1B). Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed infiltrative lesions and mucosal edema with T1 enhancement in the left nasal vestibule and anterior nasal cavity. In the inversion recovery image, an infiltrating inflammatory lesion with non-uniform high signal intensity was observed (Fig. 2). On the final biopsy, HSV type-1 was identified in both the left nasal vestibule and the left inferior turbinate mucosa, and no evidence of fungal infection was found. Then, the administration of an antiviral agent (acyclovir) was initiated. However, the recovery of the mucosal lesion was slow. Since there was a history of previous intranasal fungal infection confirmed and the patient was in a state of persistent immunosuppression, debridement under general anesthesia and mucosal flap of the middle turbinate in the mucosal defect were additionally performed to exclude AIFI mixed infection. However, the second biopsy in hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (Fig. 3) and immunostaining in both the left vestibular and inferior turbinate mucosa confirmed only HSV type-1 infection, and there was no evidence of fungal infection. Although intravenous administration of antiviral agent and application of antiviral ointment were continued, mucosal lesions of the nasal cavity and skin lesions around the nose were maintained without significant change at first. Then, the administration of intravenous antiviral drugs was stopped after 3 weeks, and the topical antiviral was in continued use. Although skin and mucosal lesions improved later, the hematopoietic stem cell transplantation failed. As a result, the patient died from sepsis and intraparenchymal hemorrhage.

A 76-year-old male patient undergoing chemotherapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma was referred to the otolaryngology department after developing painful ulcerative lesions in the oral and nasal cavity. The patient complained of nasal pain with no other nasal symptoms and had no history of diagnosis and surgery for rhinosinusitis. On endoscopic examination, a large amount of erythematous skin changes and hemorrhagic crusts were observed in the anterior part of the right nasal septum and vestibule. When the crusts were removed in the anterior part of the right nasal septum, an ulcerative lesion accompanied by mucosal edema and pallor was confirmed (Fig. 4A). In the oral cavity, multiple ulcers with erythematous changes were found on the dorsal part of the tongue, hard palate, and bilateral lateral pharynx. As AIFI was suspected, biopsies were performed for mucosal lesions in the nasal vestibule, nasal septum, and nasal cavity, respectively. However, there was no evidence of fungal infection confirmed in the frozen section biopsy. Although soft tissue swelling was found in the right nasal cavity adjacent to columella based on computed tomography, there was no evidence of infiltration into the surrounding fat surface or bone erosion (Fig. 5A). Based on the treatment experience of the previous patient, HSV infection was suspected of diffuse mucosal lesions of the oral and nasal passages, and an antiviral agent (acyclovir) was administered intravenously for 1 week. In the final report of biopsy including immunostaining, HSV type-1 was identified and there was no evidence of fungal infection. After intravenous antiviral administration, there were improvements in erythematous skin changes in the nasal septum and nasal vestibules, as well as crusts and erosive mucosal lesions. After discharge, the drug was switched to oral antiviral drug (valacyclovir), and skin and mucous membranes were almost normalized (Fig. 4B). The computed tomography also confirmed the improvement of edema in the right nasal vestibule and intranasal mucosal membrane (Fig. 5B).

HSV is a double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid virus with a pathophysiology of latent infection in neural tissues such as dorsal root ganglion, sympathetic ganglion, and peripheral nerve after primary infection, and is activated depending on the systemic and immune status. In the head and neck area, the infection occurs due to gingivostomatitis, pharyngotonsillitis, and eye infection [3]. Clustered blisters, erythematous changes, and crusts are observed after the infection and accompanied by symptoms such as pain, itchiness, and burning sensation. However, atypical clinical features can be exhibited [4] in immunocompromised patients and may be expressed similarly to AIFI with a high mortality rate.

Differentiating between HSV infection and AIFI is very critical because AIFI has only 50%–60% of a 6-month survival rate [1,5] and treatments such as rapid antifungal treatment, early debridement of mucosal lesions, and correction of underlying diseases are important for prognosis [6]. In fact, it is reported in some papers that early debridement and rapid recovery of absolute neutrophil counts improve the survival rate of AIFI [1,7,8].

AIFI is characterized by mucosal edema, pallor, dry nasal mucosa, necrotic tissue, and repeated intranasal crusts, and concentrated mucus of green, brown, or gray color may be observed when accompanied by rhinosinusitis [3]. For immunocompromised patients, AIFI is accompanied by ocular invasion in about 32%, and the 6.5% may progress as intracranial invasion. Such complications can be evaluated through magnetic resonance imaging. In computed tomography, symptoms such as nasal and sinus mucosal edema similar to bacterial sinusitis and bone erosion in the late stage of infection can be confirmed. However, the diagnostic value of imaging tests for AIFI is not high due to the low sensitivity and specificity of tests [9].

Therefore, it is necessary to preferentially identify AIFI by synthesizing risk factors and underlying disease history when nasal skin and intranasal mucosal lesions with necrotic change occur in the nose of immunocompromised patients, rather than simply referring to clinical findings or imaging tests, and then perform a frozen section biopsy to check the presence of fungi in the tissue for a quick and accurate diagnosis. Unlike HSV infection, infiltration of inflammatory cells is not usually observed in H&E staining, and fungi mixed with fibrous tissue in the blood vessel wall and intravascular space can be more easily distinguished in silver staining and periodic acid-Schiff staining. In 30% of AIFI patients, the fungal culture can be tested negative. Then, in situ hybridization for the pathological tissue makes it possible to confirm the fungal infection even when the culture test comes out negative and identify the type of fungal infection [10–12]. HSV infection can also be differentiated by pathologic findings after biopsy, but in some patients, clinical and simple pathological findings do not provide sufficient diagnostic evidence and additional inspections may be performed such as staining, Tzank smearing, virus culture test [4]. They are pathologically characterized by cell degeneration such as enlarged and pale keratinocytes with steel gray nuclei, marginated chromatin, multinucleated cells, and eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion. When tissue is accompanied by necrosis, the infection is not limited to the epidermis, but invades the structure of the body such as sebaceous glands and hair follicles in the dermis, and a large number of inflammatory cells are infiltrated. For this case, it is necessary to differentiate it from benign skin lesions such as hematological tumors, lupus, rosacea, erythema multiforme, and Wegener’s granulomatosis and performing staining using HSV PCR swab, in situ hybridization, HSV antibody allows detailed and accurate diagnosis including virus subtypes (type 1 and 2). In the case of serological tests, it is highly likely to be false-positive as most people possess high levels of HSV antibodies. Therefore, a single serological test is not effective in diagnosis [4,13].

The authors performed frozen-section biopsy with suspicion of AIFI for necrotic lesions of the nasal skin and intranasal mucosa in immunocompromised patients. Based on the result, there was no fungal infection in both cases and the final biopsy confirms the infection as HSV type-1. However, these cases were different from typical HSV skin infection as they were not accompanied by characteristic blisters or severe hemorrhagic lesions. The scope of the lesions in both cases was not limited to mucosal edema and ulcerative changes in the nasal and nasal septum, and erythematous changes and hemorrhagic scabs were accompanied in the skin around the nose including the nasal tip and alar rim. For both cases, ulcerative lesions accompanied by lesions were identified when scabs were removed. Unlike AIFI, which mainly showed crusts accompanied by old clots, these hemorrhagic lesions were characterized by mixed fresh blood. In both cases, ulcerative lesions accompanied by pallor and erythematous changes were additionally confirmed in the oral cavity and gums in both cases. This is consistent with the fact that HSV type-1 is most commonly expressed as gingivostomatitis [3], and it does not show typical herpetiform lesions or prodromal symptoms when the rare infection of the nasal mucosa occurs [14]. Therefore, if intranasal mucosal lesions are found in immunocompromised hosts, confirming whether the presence of skin lesions in nasal cavity adjacent to columella outside the mucosa and oral mucosal lesions are present will be a clue to distinguish HSV infection from AIFI. However, for immunocompromised patients, oral mucosal lesions accompanied by ulcerative changes can also be caused by other etiologies such as Epstein-Barr virus and Cytomegalovirus besides HSV infection and can also occur in oral mucositis and aphthous stomatitis after chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Therefore, careful examination is necessary [3].

The prognosis is usually good for HSV infection as in case 2 if intravenous infusion of an appropriate antiviral agent, application of topical ointment, and correction of underlying diseases and immune-decreasing factors are combined together, and other papers also confirm the improvement within 2 weeks [13,15]. Therefore, if there was no fungus in the frozen section biopsy for the nasal lesions in immunocompromised patients, immunostaining or HSV intranasal polymerase chain reaction smear should be performed to identify HSV infection. Proactive antiviral treatment can lead to a positive clinical prognosis.

Since the number of reported cases of nasal skin and intranasal HSV infection in immunocompromised patients is not large at home and abroad [13,15], the authors performed biopsy and imaging tests with suspicion of AIFI. When necrotic lesions on the nasal mucosa and skin around the nose were expressed in immunocompromised hosts through the diagnosis and treatment process of case 2, they tried to provide clinical clues for diagnosis and therapeutic approaches. We believe this discussion is clinically meaningful.

Notes

Ethics Statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center (IRB No. 2022-07-102-001), and the requirement of informed consent was waived.

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Yong Gi Jung. Methodology: Changhee Lee. Project administration: Changhee Lee. Supervision: Yong Gi Jung. Validation: Yong Gi Jung, Hyo-Yeol Kim, Sang Duk Hong. Visualization: Changhee Lee. Writing—original draft: Changhee Lee. Writing—review & editing: Yong Gi Jung.

Fig. 1

Endoscopic finding of patient 1. A: Hemorrhagic crusts on an erythematous base are seen from columella, subnasale to alar rim in left nose. Ulcerative mucosal lesion with edema and pallor extends from anterior septum and lateral mucosa to inferior turbinate in left nasal cavity. B: New ulcerative lesions and pallor in lower lip, upper lip, anterior tip of tongue and right maxillary second molar adjacent gingiva (white arrows).

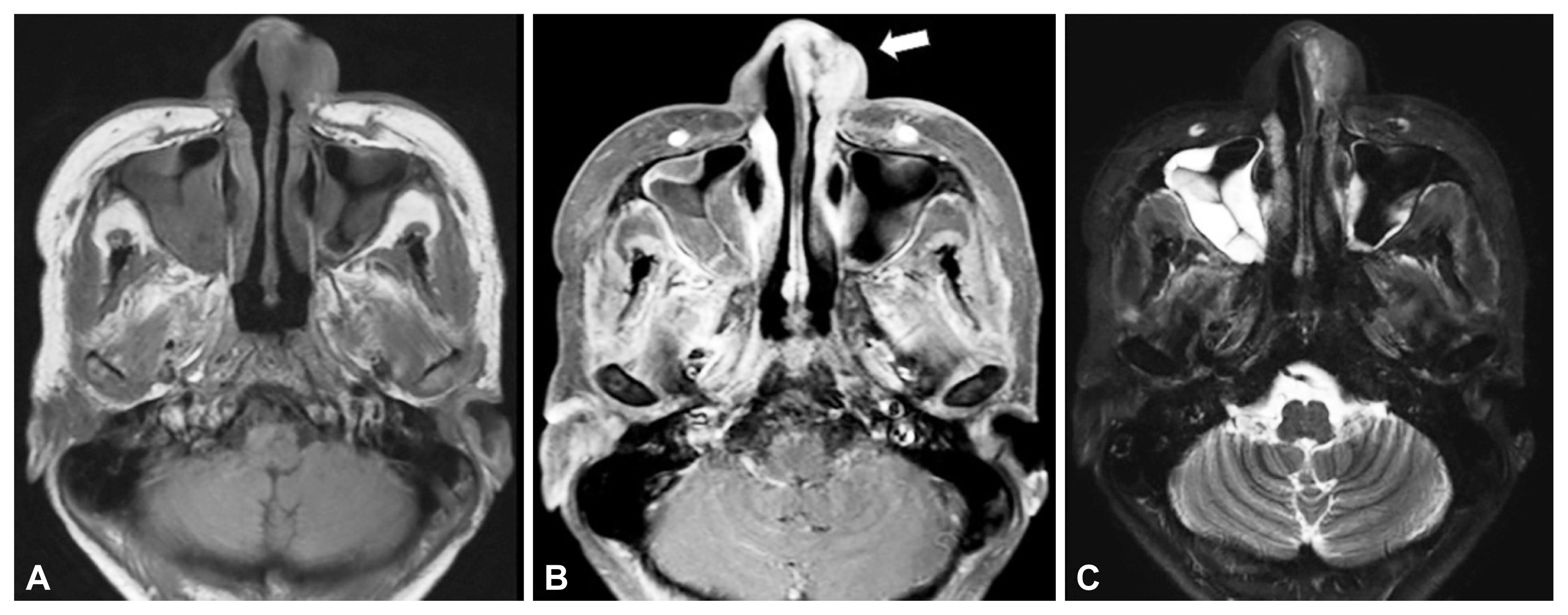

Fig. 2

MRI finding of patient 1. A: T1-weighted image. B: T1-enhanced image showing soft tissue infiltrative lesion by invasive herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection (white arrow) in left anterior nasal cavity and vestibule. C: Short TI-inversion recovery image.

Fig. 3

Pathologic finding of patient 1. A: H&E staining (×200). B: H&E staining (×400). Mixed inflammatory infiltration, multinucleated giant cells (white arrow) and intranuclear inclusion (black arrow) are seen.

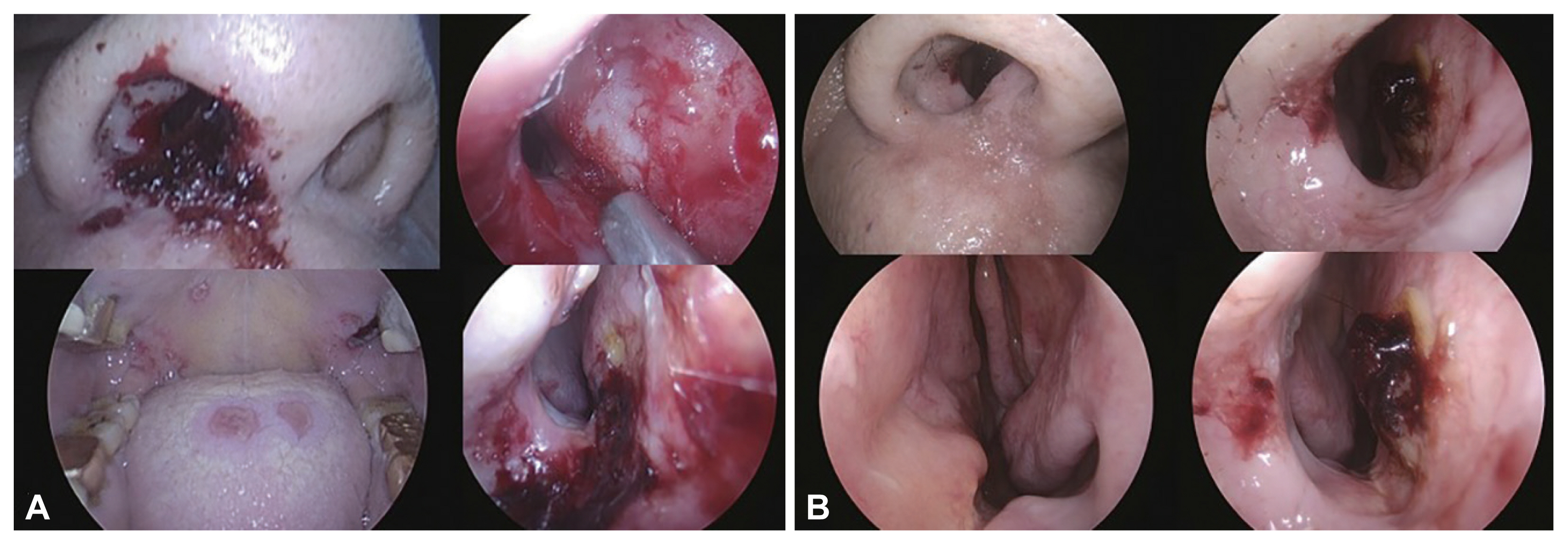

Fig. 4

Endoscopic findings of patient 2. A: Before antiviral treatment. Hemorrhagic crusts on an erythematous base are seen along to subnasale and columella in right nose. Ulcerative mucosal lesions and pallor are also seen along anterior septum in right nasal cavity. Multiple ulcerative lesions are seen on dorsal tongue, hard palate, and lateral pharyngeal wall. B: After antiviral treatment.

REFERENCES

1) Wandell GM, Miller C, Rathor A, Wai TH, Guyer RA, Schmidt RA, et al. A multi-institutional review of outcomes in biopsy-proven acute invasive fungal sinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2018;8(12):1459–68.

2) deShazo RD, O’Brien M, Chapin K, Soto-Aguilar M, Gardner L, Swain R. A new classification and diagnostic criteria for invasive fungal sinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;123(11):1181–8.

3) Montone KT. Infectious diseases of the head and neck: a review. Am J Clin Pathol 2007;128(1):35–67.

4) Hoyt B, Bhawan J. Histological spectrum of cutaneous herpes infections. Am J Dermatopathol 2014;36(8):609–19.

5) Turner JH, Soudry E, Nayak JV, Hwang PH. Survival outcomes in acute invasive fungal sinusitis: a systematic review and quantitative synthesis of published evidence. Laryngoscope 2013;123(5):1112–8.

6) Yohai RA, Bullock JD, Aziz AA, Markert RJ. Survival factors in rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis. Surv Ophthalmol 1994;39(1):3–22.

7) DelGaudio JM, Clemson LA. An early detection protocol for invasive fungal sinusitis in neutropenic patients successfully reduces extent of disease at presentation and long term morbidity. Laryngoscope 2009;119(1):180–3.

8) Rizk SS, Kraus DH, Gerresheim G, Mudan S. Aggressive combination treatment for invasive fungal sinusitis in immunocompromised patients. Ear Nose Throat J 2000;79(4):278–80. 282284–5.

9) DelGaudio JM, Swain RE Jr, Kingdom TT, Muller S, Hudgins PA. Computed tomographic findings in patients with invasive fungal sinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;129(2):236–40.

11) Montone KT, Livolsi VA, Feldman MD, Palmer J, Chiu AG, Lanza DC, et al. Fungal rhinosinusitis: a retrospective microbiologic and pathologic review of 400 patients at a single university medical center. Int J Otolaryngol 2012;2012:684835.

12) Montone KT. Differential diagnosis of necrotizing sinonasal lesions. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2015;139(12):1508–14.

13) Patel NA, Kessel R, Zahtz G. Herpes simplex virus of the nose masquerading as invasive fungal sinusitis: a pediatric case series. Am J Otolaryngol 2019;40(4):609–11.

-

METRICS

-

- 1 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

- 1,865 View

- 52 Download

- Related articles

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print