INTRODUCTION

There are many surgical paths to the maxillary sinus. If the lesion lies on the anterior side or floor of the maxillary sinus, surgery featuring a large middle meatal antrostomy is often associated with a limited visual field. Good visibility is essential for the en bloc resection of recurrent lesions, such as inverted papilloma (IP). When approaching the maxillary sinus, the Caldwell-Luc procedure, lateral rhinotomy, midfacial degloving approach, and endoscopic medial maxillectomy are widely used; however, various complications of such approaches are well known.

Recent studies have introduced a prelacrimal window approach (PLWA) to preserve the turbinate and lacrimal apparatus and have found that the prelacrimal or alveolar recess can be accessed [

1,

2]. Suzuki et al. [

3] analyzed the utility of a modified transnasal endoscopic medial maxillectomy (TEMM) approach, which preserves the inferior turbinate and shifts the lacrimal duct medially. Recurrence occurs only in 1 of 51 patients who underwent surgery to remove an IP; the inferior turbinate was preserved without atrophy, and no deformity was observed. Some patients required partial osteotomy of the apertura piriformis or the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus, but the procedure was nonetheless safe and effective.

Simmen et al. [

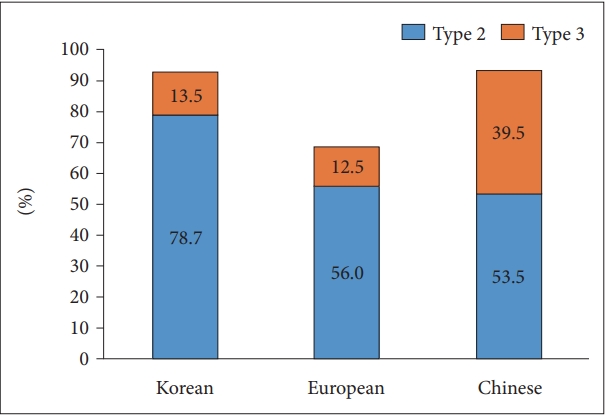

4] used computed tomography (CT) to analyze anatomical variations in the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus and the lacrimal apparatus and suggested that surgeons should evaluate the difficulty of PLWA before surgery. If the distance between the anterior walls of the maxillary sinus and lacrimal duct (D1) was 0–3 mm (type 1), a significant amount of bone resection and temporary dislocation or resection of the lacrimal duct was required to access the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus. Even if a window is created, it is small and compromises full access. When D1 was >3–7 mm (type 2), the sinus was accessible, but partial dislocation of the lacrimal duct may be required. Type 3 D1 (>7 mm) allows easy access to the maxillary sinus. A previous study in Europeans population reported that the frequencies of types 1, 2, 3 were 31.5%, 56.0%, and 12.5%, respectively, thus, the type 2+3 was 68.5%. Lock et al. [

5] analyzed 200 CT scans from 100 Chinese patients; the frequencies of types 1, 2, and 3 D1 were 6.5%, 53.5%, and 39.5%, respectively; the ease of the PLWA was 93.0% (type 2+3). Based on these results, it has been suggested that Asians exhibit more paranasal sinus (PNS) pneumatization than Europeans. However, none of the studies evaluated healthy controls.

This study aimed to compare the ease of the PLWA between the patient group and healthy controls and analyze the results for Koreans and those of previous studies. The differences between the patient and control groups and the distribution of types in the Korean population were also evaluated.

DISCUSSION

Maxillary sinus lesions may be approached using the Caldwell-Luc technique, lateral rhinotomy, and midfacial degloving. Endoscopic medial maxillectomy has recently become popular because it is less invasive than other methods. However, endoscopic medial maxillectomy may damage the inferior turbinate or lacrimal duct, resulting in complications such as crusting or epiphora. In addition, access to the anterior wall and floor of the maxillary sinus is limited. In 2007, Zhou et al. [

1] introduced a technique to preserve the inferior turbinate and lacrimal apparatus. In 2011, Suzuki et al. [

3] reported a similar procedure referred to as TEMM, which preserves the inferior turbinate and shifts the lacrimal duct medially, allowing complete resection of maxillary sinus lesions. Simmen et al. [

4] suggested that the ease of a PLWA could be determined by measuring the distance between the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus and the lacrimal apparatus, allowing the surgeon to plan an approach. Compared with open approaches, PLWA provides better vision and surgical access to the anterior wall and floor of the maxillary sinus, with lower morbidity and recurrence rates.

In general, it is known that Asian heads have shorter front and rear lengths than those of European. However, in this study, D1 of Koreans and Chinese was measured to be longer than D1 of Europeans. And the type 2+3 frequency was also higher than Europeans. This shows that the difference in head length between Asians and Europeans does not reflect the differences in the anatomical lengths of all organs inside the head. Indeed, looking at the examples of other organs, Moon et al. [

6] introduced that the length of the orbital floor did not statistically significantly different between race. Similarly, when looking at this study and the previous study [

4,

5] together, it can be seen that the length of D1 for Asians is generally longer than D1 for European. More follow-up studies are needed to determine the exact cause of this occurrence.

In our study, the frequencies of types 1, 2, and 3 were 6.9% (7/102), 78.4% (80/102), and 14.7% (15/102), respectively, in the control group and 10.3% (4/39), 79.5% (31/39), and 10.3% (4/39), respectively, in the patient group; no significant differences were observed between the two groups (p=0.697) (

Table 3). The T of the patient group was significantly greater than that of the control group. The most common location of IP is the lateral nasal wall, and the second is maxillary sinus, which causes local hyperostosis, resulting in a difference in T [

7]. In addition, the T appears to have thickened due to bone changes caused by inflammation.

The frequency types in Korean, Europeans, and Chinese populations were 7.8%, 31.5%, and 6.5%, respectively, for type 1; 78.7%, 56%, and 53.5%, respectively, for type 2; 13.5%, 12.5%, and 39.5%, respectively, for type 3 (

Fig. 3). In our study, 92.2% of patients were classified as type 2+3; a PLWA is very feasible. The frequencies for Europeans and Chinese were 68.5% and 93.0%, respectively; the PLWA may be more appropriate for Chinese than for Europeans. We found that our results in the Korean population were more similar to the Chinese than European. Therefore, we can suppose that there is high feasibility of PLWA in Northeast asians.

There were some limitations to this study. First, this study include the small number of participants. Further studies are needed in patients with other tumor lesions affecting the anterior wall and floor of the maxillary sinus. Second, despite excluding those who lacked anatomical landmarks, CT images were obtained by reconstruction at a slice thickness of 2 mm, so it had some measuring error. These factors could limit accurate measurement.

In conclusion, D1 and D2 of the patient group did not differ from the control group, and T was greater in the patient group. In the patient group, D1 and D2 were not significantly different between sinus with IP and normal sinuses. The frequency of patients with type 2+3 was similar to that of the control group. The D1 distribution in Koreans was similar to that in Chinese. The ease of a PLWA was 92.2% (type 2+3), which is more similar to that of the Chinese than the European patients. In Korea, when the lesion is the anterior portion of the maxillary sinus, the PLWA technique is recommended more actively.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print