|

|

| J Rhinol > Volume 29(1); 2022 |

|

Abstract

Background and Objectives

Osteomas are the most common benign tumors of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses (PNSs). In this study, clinical features and imaging findings were analyzed in patients with osteoma confirmed by ostiomeatal unit (OMU) computed tomography (CT) and PNS CT, and the surgical treatment performed at our hospital was introduced.

Methods

The Severance Clinical Research Analysis Portal (SCRAP) service of Severance Hospital was used to collect research data. A total of 128 cases of osteomas of the nasal cavity or PNSs confirmed by OMU CT or PNS CT was retrospectively reviewed, including the location and size of the osteoma, clinical features, accompanying findings on imaging tests, and cases of surgical treatment.

Results

In this study, osteomas were found in about 0.55% of patients who underwent computed tomography. Osteomas were most frequently found in the ethmoid sinus, followed by the frontal sinus, fronto-ethmoid sinus, maxillary sinus, intranasal sphenoid sinus, and maxillary sinus-ethmoid sinus. Patients with osteomas complained of symptoms such as rhinorrhea, postnasal drip, nasal congestion, hyposmia, headache, visual disturbance, and lacrimal duct obstruction.

Osteomas are the most common benign tumors of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses (PNSs), and are found in about 1%–3% patients who undergo computed tomography (CT). They can occur at any age but are mainly found in patients in their 40s and 60s. The cause of osteomas is still unknown, but they are thought to be a result of the development process, trauma or infection [1,2].

Thin slice CT is used for the diagnosis of osteomas, as it has advantage of being able to provide additional information such as accompanying sinus diseases, on top of anatomical location and size of the osteoma [3].

Most osteomas are asymptomatic, but may cause various symptoms depending on their location and size. The most common symptom is headache, and others include nasal congestion, local pain, and ocular symptoms such as epiphora, exophthalmos, and visual field disturbance. In the case of an asymptomatic or small osteoma, regular follow-up is sufficient, but in the case of a symptomatic osteoma, surgical removal is generally performed as the primary treatment [4,5].

In this study, clinical features and imaging findings were analyzed in patients with osteoma confirmed by ostiomeatal unit (OMU) CT or PNS CT with a review of the existing literature. In addition, we aim to share our own treatment experience through several cases of our institution.

This study was conducted on 23,065 patients who visited Yonsei University College of Medicine Severance Hospital with sinus disease and underwent OMU CT and PNS CT during the period of 15 years from September 1, 2005 to August 31, 2020.

The Severance Clinical Research Analysis Portal (SCRAP) service of Severance Hospital was used to collect research data after obtaining (IRB No. 4-2021-0908). In 128 cases of osteomas of the nasal cavity or PNSs confirmed by OMU CT or PNS CT, the location and size of the osteoma, clinical features, accompanying findings on imaging tests and cases of surgical treatment were reviewed retrospectively. For those patients with symptomatic osteomas who required surgical treatment, external or endoscopic approach was determined depending on the location and size of the tumor. Endoscopic approach was performed using a navigation system.

Among 23,065 patients who underwent OMU CT or PNS CT at our hospital for the 15 years from 2005 to 2020, there were 128 cases (0.55%) in which an osteoma was found in the nasal cavity or PNSs. The average age of the patients was 50.8±15.3 years, from 18 to 76 years old, and the ratio of females to males was 1.17:1, with females (53.9%) and 59 males (46.1%).

Of the 128 cases, 120 cases presented with a single lesion, and the other 8 cases presented with two or more multiple lesions. The osteoma was located on the left side in 63 cases, on the right side in 59 cases, bilaterally in 5 cases and in the middle in 1 case. The ethmoid sinus accounted for 70 cases, which was the largest number of cases, followed by 42 cases in the frontal sinus, 7 cases in the frontal and ethmoid sinuses, 5 cases in the maxillary sinus, 2 cases in the nasal cavity, 1 case in the sphenoid sinus, and 1 cases in the maxillary sinus-ethmoid sinus (Table 1). The average size of the osteoma was 1.4±0.95 cm, from a minimum of 0.4 cm to a maximum of 4.0 cm.

The most common symptom reported by patients with an osteoma was rhinorrhea in 41 patients (32.0%), postnasal drip in 25 patients (19.5%), nasal congestion in 28 patients (21.9%), hyposmia in 20 patients (15.6%), headache in 19 patients (14.8%), epistaxis in 2 patients (1.6%), visual disturbance and lacrimal duct obstruction in 1 patient (0.8%) each (Table 2). In the imaging test results, sinusitis was combined in a total of 83 cases (64.8%). Of these, 17 cases (13.3%) had sinusitis on ipsilateral side as the osteoma, and 7 cases (5.5%) on contralateral side of the osteoma. There were 49 cases (38.3%) with bilateral sinusitis. In addition to sinusitis, there was septal deviation in 65 patients (50.8%), a lamina papyracea defect in 8 patients (6.3%), a retention cyst and concha bullosa in 6 patients (4.7%), Haller’s cells in 2 patients (1.6%), and single instances (0.8%) of nasal bone fracture, exophthalmos, and septal perforation (Table 3).

Endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) was performed for accompanying sinusitis in 25 cases (19.5%). Of the 25 patients who underwent surgery, 18 (72.0%) showed an osteoma at the ethmoid sinus on preoperative CT, 5 (20.0%) at the frontal sinus, 3 (12.0%) at the fronto-ethmoid sinus and 1 (4.0%) at both the ethmoid and maxillary sinuses. Out of 25 patients who underwent ESS, osteoma was found to be the critical cause of sinusitis in 4 patients (16.0%). All of these osteoma were located in ethmoid or frontal sinus and surgically removed during ESS.

There were 3 cases that required surgical treatment for symptomatic osteoma itself. In two cases, headache was caused by frontal sinus osteoma. In the other case, an osteoma and mucocele were compressing on the optic nerve and causing visual field disturbances and required emergency treatment.

The cases in which osteoma was surgically removed are summarized in Table 4. We would like to share our experience through some of these cases. The first case, a 42-year-old male patient, visited the emergency medical center with an acute headache that had started 3 days before admission. Endoscopy and CT showed osteoma occupying the right frontal sinus (Fig. 1). The patient’s pain could not be controlled, and surgical treatment was required. Since the osteoma was occupying most of well-pneumatized frontal sinus and it was attached to the far-lateral sinus, a lynch incision was performed from the right eyebrow to the medial canthus and frontal sinus incision, and osteoma volume reduction was done using a drill. The pathology report was consistent with osteoma and, the patient had no residual symptoms for 15 months after the surgery, during which period, regular follow-up was performed (Fig. 1).

The second case, a 25-year-old female patient, was referred from the ophthalmology department because of a left eye protrusion and astigmatism that started 1 to 2 years previously. An osteoma of 2.48×4.18×3.22 cm in size was discovered on the CT OMU. This osteoma was compressing the optic nerve and forming a sphenoid sinus mucocele (Fig. 2). Due to the left eye optic neuropathy, emergency surgery was performed. During the operation, the ethmoid sinus cells were not visible due to the osteoma. The osteoma around the entrance of the sphenoid sinus was removed using a drill, and the mucous components were drained. Although there was no significant improvement in the patient’s visual field symptoms after surgery, the drainage of the sphenoid sinus was successful (Fig. 2).

For asymptomatic osteomas, regular follow up with physical examination and image study is sufficient. A 47-year-old female visited outpatient clinic due to incidental finding of osteoma. An osteoma about 2 cm in size was found in the maxillary sinus (Fig. 3). Because it was located on the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus, it did not cause any symptom to the patient. Therefore, without any special treatment the patient visits our clinic regularly for physical examination and CT scan.

Osteoma is the most common benign tumor of the nasal cavity and PNSs [1,6] and is a slow-growing fibrosing lesion with an average growth rate of about 1 mm (0–6 mm) per year [7,8]. It is known to be found in about 1%–3% of patients who have had CT of the PNS [2,9]. In this study, osteomas were found in 128 cases out of 23,065 cases that had CT performed, and showed a prevalence of about 0.55%. However, all these cases were patients who had visited the hospital with symptoms such as rhinorrhea and nasal congestion. Since we only analyzed cases with osteoma discovered by CT reading, there is a limit to discussing the prevalence based on this study.

Osteomas can occur at any age, but they are mainly found in those in their 40s and 60s [2] and are either more common in men or there is no difference between the sexes depending on the research being reviewed [10,11]. In this study, the average age of patients with osteoma was 50.8 (±15.3, 18–76) years, which was consistent with previous literature. There were 59 cases of osteoma in men and 69 cases of osteoma in women, showing a somewhat higher rate in women (1.17:1).

Although the cause of osteomas is not yet clear, there is a hypothesis that bone remodeling occurs excessively due to trauma or infection [1,12], and there is a hypothesis that it is caused by abnormalities in the embryonic development process. Some suggest sporadic osteoma occurance often a result of bone hyperplasia in the area where the cartilaginous part of the ethmoid bone contacts the membrane of the frontal sinus, and anatomical variation, such as Haller cells or pneumatization of the cribriform plate, is significantly higher in patients with an osteoma [13]. In this study, 65 (50.8%) of 128 cases were accompanied by septal deviation, 8 cases (6.3%) were accompanied by lamina papyracea dehiscence, there were 6 cases each (4.7%) of concha bullosa and retention cyst, and 2 cases (1.6%) of Haller cells associated with osteomas.

Thin slice CT is usually performed for the diagnosis of osteomas. Osteomas show characteristically dense cortical bone and ground glass opacity on CT images. Previously, they were thought to be found most commonly in frontal sinus [3], but some recent studies have shown that they are in fact found more commonly in ethmoid sinus [2,9]. In this study, osteomas of the ethmoid sinus were the most common with 70 cases, while there were 42 cases in the frontal sinus, 7 cases in the frontal and ethmois sinus simultaneously, 5 cases in the maxillary sinus, 2 cases in the nasal cavity, and 1 case in each of the sphenoid and maxillary-ethmoid sinuses. One previous study suggests that development of osteomas occur most frequently at the junction between the ethmoid sinus and the frontal sinus [13].

Most osteomas do not produce any symptoms due to their slow growth rate and are often found incidentally on imaging tests. However, 4%–10% of patients have symptoms depending on the location or size of the osteoma. A common symptom associated with osteomas is headache, localized pain and ocular symptoms such as epiphora, exophthalmos, and visual field disturbance depending on the extent of spread [4]. In this study, the most common symptom of osteoma patients was rhinorrhea, which was reported in 41 patients (32.0%), post nasal drip in 25 patients (19.5%), nasal congestion in 28 patients (21.8%), hyposmia in 20 patients (15.6%), headache in 19 patients (14.8%), epistaxis in 2 patients (1.6%), and visual disturbance and lacrimal duct obstruction in 1 patient each (0.8%). These results may contain bias because the testing was conducted on patients who visited the hospital with certain rhinologic symptoms, not the entire population. Since most of these patients had accompanying diseases, such as sinusitis and septal deviation, the symptoms may be different from those caused by the osteoma alone.

If an osteoma is located in the ethmoid sinus or frontal sinus, it may inhibit mucus drainage in the frontal sinus and cause sinusitis [9]. Similarly, in this study, osteoma was accompanied by sinusitis in 83 patients (64.8%) which was a significant percentage, with 17 cases on the ipsilateral side, 7 cases on the contralateral side, and 49 cases on both sides. There were 27 patients who underwent surgery for sinusitis, of which 18 (66.7%) had osteomas located in the ethmoid sinus, 5 (18.5%) in the frontal sinus, 3 (11.1%) in the frontoethmoid sinus and 1 (3.7%) in the maxilla-ethmoid sinus. This result is consistent with previous research that reported osteomas located in the ethmoid sinus could be the cause of sinusitis.

In the case of asymptomatic or small osteoma, regular follow-up with physical examination, nasal endoscopy, and regular imaging tests is sufficient. In any of these subsequent radiological follow-ups, if the tumor appears to grow with a mean rate of more than 1 mm/year, then excision of the osteoma should be considered [4]. If the osteoma is causing symptoms such as headache, localized pain, facial deformity, rhinorrhea or secondary symptoms due to mucocele formation, surgical removal may be needed [5]. In particular, when an osteoma invades the base of the skull or is accompanied by complications, such as epiphora, diplopia, orbital infection, and visual field disturbance, surgical treatment is required [14,15]. Surgery can be performed by both endoscopic and external approaches. When applicable, an intranasal endoscopic approach is rightful and advisable, because an open approach subjects the patient to increased morbidity and a longer recovery course. Endoscopic resection should be, nowadays, considered the optimal approach for almost every ethmoidal osteoma or a frontal sinus osteoma with median localization.

In previous studies, the surgical method has been suggested by calculating the grade based on the location and size of the osteoma in imaging tests such as CT. Chiu et al. [16] in 2005, whereby they tried to define the grade of frontal sinus osteoma using variables restricting the applicability of an endoscopic removal.

Sofokleous et al. [17] proposed revised grading system based on thorough review of the articles of the past 30 years. They classified any osteoma with a base of attachment located at or near the area of the frontal recess and tumor remains medial to a virtual sagittal plane passing through the lamina papyracea as grade I. These tumors are amenable to endoscopic resection. Grade II osteoma has its point of attachment anteriorly or superiorly within the frontal sinus or tumor extends laterally to a virtual sagittal plane that passes tangentially through the lamina papyracea. These are also manageable through an endoscopic approach. However, they suggest the potential for conversion to an open approach should be discussed beforehand. Grade III tumors correspond to massive tumors that fill the entire frontal sinus or tumors with a point of attachment in the far-lateral aspect of a well-pneumatized frontal sinus. These tumors are excellent candidates for an open approach. Endoscopic resection may be achievable, but this requires auxiliary approaches, and techniques may be needed such as ‘orbital transposition technique’ or the ‘two nostrils four hands technique’ [18,19]. Grade IV osteomas are tumors with intracranial or far anterior intraorbital extension, attached to orbital roof at a location lateral to the midorbital point, adverse anatomical factors that may restrict access, therefore currently thought of as not amenable to an endoscopic approach.

According to the surgical treatment in our institution presented in Table 4, all osteomas of the ethmoid sinus and nasal cavity could be surgically removed using only endoscopic approach regardless of their size and location. In the case of frontal sinus osteoma, it was possible to remove grades I and II through an endoscopic approach, but in the case of grades III, the open approach was required for complete tumor removal. This result is consistent with the guidelines for surgical treatment presented above.

In conclusion, in this study, clinical features and imaging findings were analyzed in patients who had osteoma confirmed by OMU CT and PNS CT, and the surgical treatment performed at our hospital was introduced. Osteomas are the most common benign tumors in the nasal cavity and PNSs. In this study, osteomas were found in about 0.55% of patients who underwent CT. Osteomas were found with the highest frequency in the ethmoid sinus, followed by the frontal sinus, fronto-ethmoid sinus, maxillary sinus, intranasal sphenoid sinus, and maxillary sinus-ethmoid sinus. Patients with osteomas complained of symptoms such as rhinorrhea, postnasal drip, nasal congestion, hyposmia, headache, visual disturbance, and lacrimal duct obstruction. In the case of severe headache, visual field symptoms or accompanying rhinosinusitis, surgical treatment was performed. Surgical treatment included an endoscopic and an external approach. Considering the location and size of the osteoma and the accompanying lesions in the preoperative CT examination, an endoscopic or external incision approach, or a combination of the two methods was performed.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

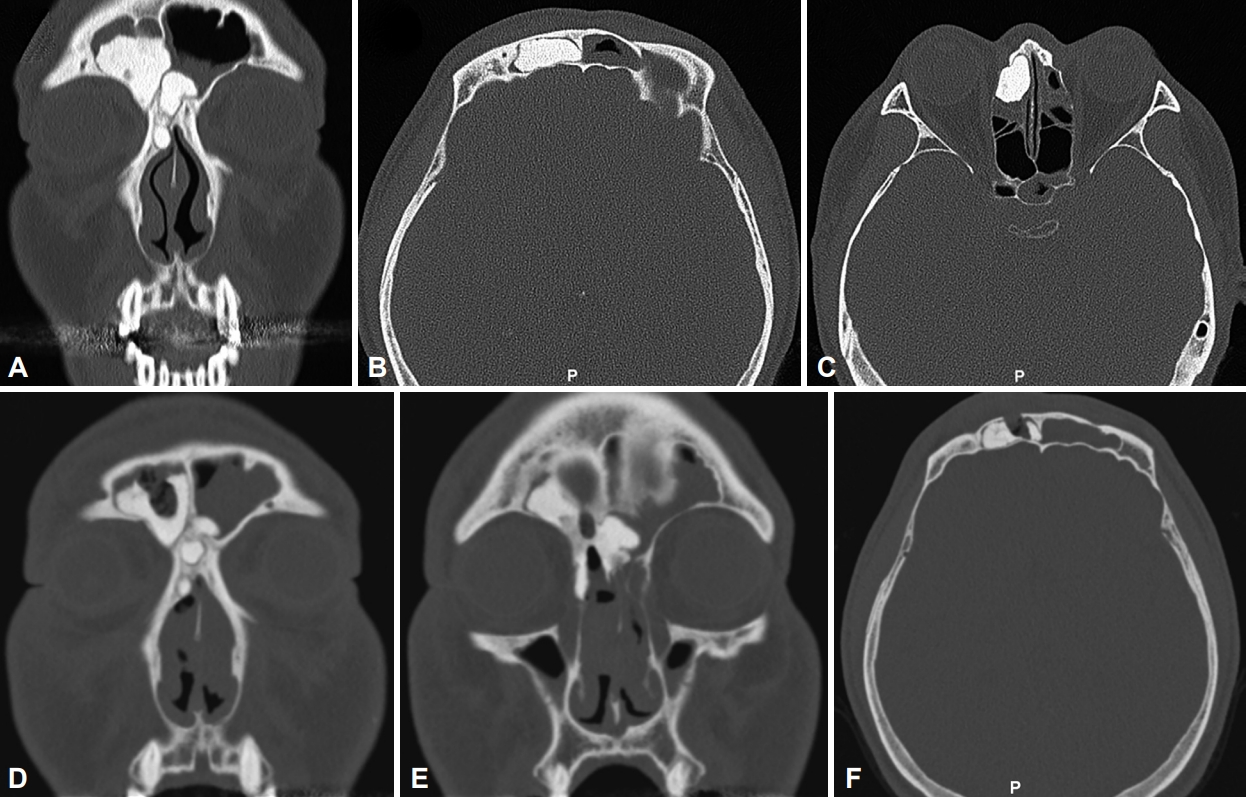

Fig. 1.

CT scan of the 42-year-old male patient. A-C: Pre-operative CT scan. An osteoma filling the right frontal sinus and posterior ethmoid sinus was discovered. D-F: Post-operative CT scan at 15 months follow-up. A, D, E: Coronal view. B, C, F: Axial view. CT, computed tomography

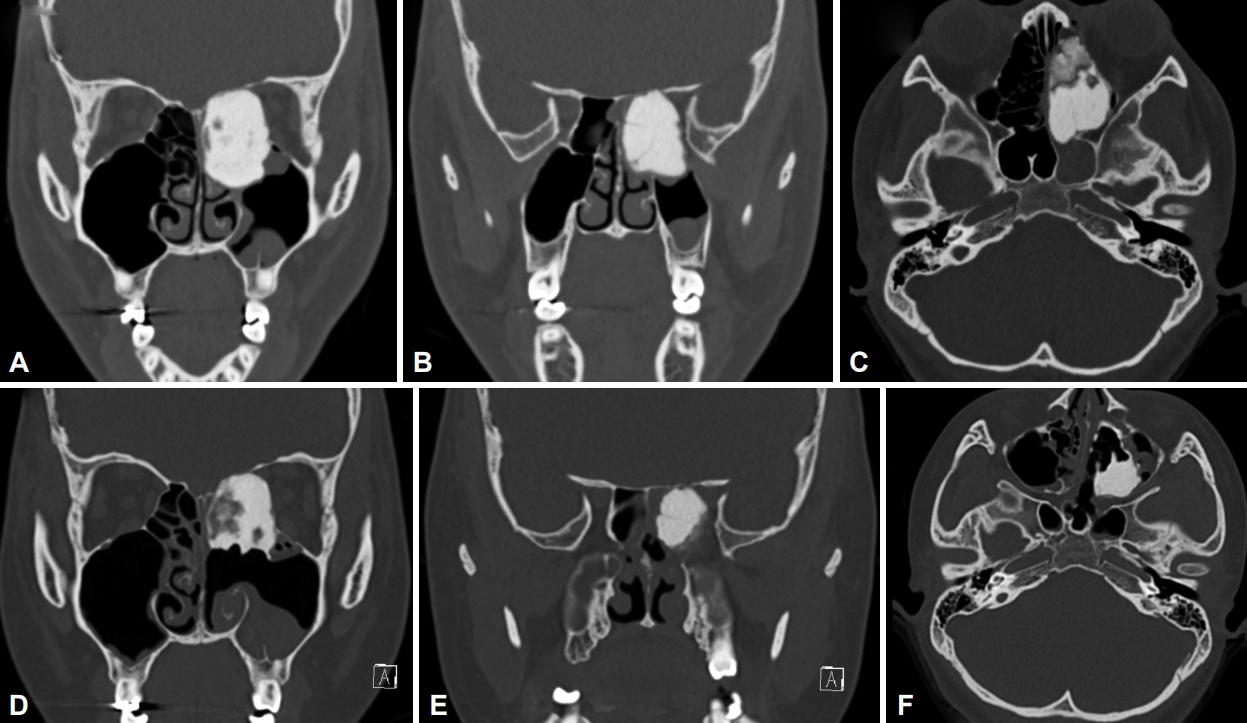

Fig. 2.

CT scan of 25-year-old female patient. A-C: Pre-operative CT scan. An osteoma of 2.48×4.18×3.22 cm in size was compressing the optic nerve and forming a sphenoid sinus mucocele. D-F: Post-operative CT scan at 13 months follow-up. A, B, D, E: Coronal view. C, F: Axial view. CT, computed tomography.

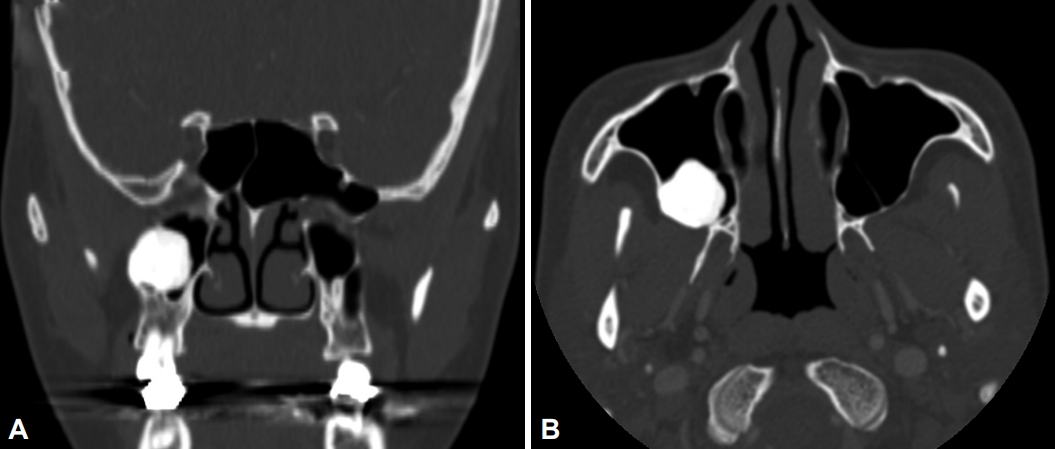

Fig. 3.

CT scan of a 47-year-old female patient who visited outpatient clinic due to incidental finding of osteoma. An osteoma about 2 cm in size of posterior maxillary sinus was noted. A: Coronal view. B: Axial view. CT, computed tomography

Table 1.

Location of osteoma (n=128)

Table 2.

Clinical symptoms of patients (n=128)

Table 3.

Accompanying findings in CT

Table 4.

Surgical treatment for paranasal sinus osteoma

| Location | Grade* | Size (cm) | Approach | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal cavity | 2.5 | Endoscopic app | ||

| Ethmoid | 1.1 | Endoscopic app | ||

| Ethmoid | 0.6 | Endoscopic app | ||

| Ethmoid | 0.6 | Endoscopic app | ||

| Ethmoid | 1.0 | Endoscopic app | ||

| Ethmoid | 3.4 | Endoscopic app | ||

| Fronto-ethmoid | I | 2.2 | Endoscopic app | |

| Fronto-ethmoid | III | 4.0 | Endo & open combined app | Lynch incision |

| Frontal | II | 2.0 | Endoscopic app | Draf IIb |

| Frontal | III | 2.0 | Endoscopic app | Sinusotomy without tumor removal |

* frontal sinus osteoma was graded using the revised grading system proposed by Sofokleous et al. [17]

References

2) Erdogan N, Demir U, Songu M, Ozenler NK, Uluç E, Dirim B. A prospective study of paranasal sinus osteomas in 1,889 cases: changing patterns of localization. Laryngoscope 2009;119(12):2355–9.

4) Çelenk F, Baysal E, Karata ZA, Durucu C, Mumbuç S, Kanlıkama M. Paranasal sinus osteomas. J Craniofac Surg 2012;23(5):e433–7.

5) Karunaratne YG, Gunaratne DA, Floros P, Wong EH, Singh NP. Frontal sinus osteoma: from direct excision to endoscopic removal. J Craniofac Surg 2019;30(6):e494.

6) Lund VJ, Stammberger H, Nicolai P, Castelnuovo P, Beal T, Beham A, et al. European position paper on endoscopic management of tumours of the nose, paranasal sinuses and skull base. Rhinol Suppl 2010;22:1–143.

7) Buyuklu F, Akdogan MV, Ozer C, Cakmak O. Growth characteristics and clinical manifestations of the paranasal sinus osteomas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2011;145(2):319–23.

8) Koivunen P, Löppönen H, Fors AP, Jokinen K. The growth rate of osteomas of the paranasal sinuses. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 1997;22(2):111–4.

9) Pons Y, Blancal JP, Vérillaud B, Sauvaget E, Ukkola-Pons E, Kania R, et al. Ethmoid sinus osteoma: diagnosis and management. Head Neck 2013;35(2):201–4.

10) Lee DH, Jung SH, Yoon TM, Lee JK, Joo YE, Lim SC. Characteristics of paranasal sinus osteoma and treatment outcomes. Acta Otolaryngol 2015;135(6):602–7.

11) Mansour AM, Salti H, Uwaydat S, Dakroub R, Bashshour Z. Ethmoid sinus osteoma presenting as epiphora and orbital cellulitis: case report and literature review. Surv Ophthalmol 1999;43(5):413–26.

12) McHugh JB, Mukherji SK, Lucas DR. Sino-orbital osteoma: a clinicopathologic study of 45 surgically treated cases with emphasis on tumors with osteoblastoma-like features. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2009;133(10):1587–93.

13) Janovic A, Antic S, Rakocevic Z, Djuric M. Paranasal sinus osteoma: is there any association with anatomical variations? Rhinology 2013;51(1):54–60.

14) Jack LS, Smith TL, Ng JD. Frontal sinus osteoma presenting with orbital emphysema. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;25(2):155–7.

15) Nguyen S, Nadeau S. Giant frontal sinus osteomas: demographic, clinical presentation, and management of 10 cases. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2019;33(1):36–43.

16) Chiu AG, Schipor I, Cohen NA, Kennedy DW, Palmer JN. Surgical decisions in the management of frontal sinus osteomas. Am J Rhinol 2005;19(2):191–7.

17) Sofokleous V, Maragoudakis P, Kyrodimos E, Giotakis E. Management of paranasal sinus osteomas: a comprehensive narrative review of the literature and an up-to-date grading system. Am J Otolaryngol 2020;42(5):102644.

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

- 3,403 View

- 81 Download

- Related articles

-

Clinical Manifestations of Postnasal Drip2002 November;9(1, 2)

Clinical Features of Bilateral Paranasal Sinus Fungus Ball2010 May;17(1)

Clinical Features and Treatment Results of 64 Cases of Nasolabial Cyst2011 May;18(1)

Headache and Facial Pain Related to the Paranasal Sinuses2012 November;19(2)

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print