|

|

| J Rhinol > Volume 28(3); 2021 |

|

This article has been corrected. See J Rhinol. 2022 Mar 28; 29(1): 59.

Abstract

Background and Objectives

The aim of the present study was to investigate the effects of a combination of crushed cartilage and thin silastic sheet for patients with a risk of septal perforation during septoplasty.

Materials and Methods

A total of 195 people who underwent septoplasty surgery at Dong-A University Hospital from January 2019 to December 2020 were enrolled retrospectively. Among 195 people, our surgical method was provided for those with damage to both septal mucosa. The cartilage was collected, crushed with the cartilage crusher, and inserted between perforated mucosa. After the cartilage insertion, a 0.254-mm-thin silastic sheet was designed to cover both sides of the perforated septal mucosa. Next, a penetrating suture was placed. After thin silastic was applied on both mucosa, a 1-mm-thick silastic sheet was inserted on both sides of the nasal cavity and penetrating sutures were placed on the anterior and inferior septum. The operation concluded after packing both sides of the nasal cavity using non-absorbable packing material. The packing was removed on the second day after the operation, and the nasal cavity condition was checked every week. Thick silastic sheets were removed 5 days after surgery, and thin silastic sheets were maintained until both septal mucosa healed.

Results

Of nine total cases, only one 78-year-old male experienced septal perforation at the cartilage portion two months after surgery. In this case, no other action was taken to cover the perforation site because he reported no symptoms or discomfort during the 9 months after surgery. In the other eight cases, both septal mucosa healed completely, and there were no complications.

A deviated septum is one of the most common causes of nasal obstruction. It can be accompanied by symptoms such as nasal bleeding and headache or worsen symptoms when combined with rhinitis or rhinosinusitis. When the cause of nasal obstruction is only a deviated septum, or when surgery for rhinosinusitis or rhinoplasty is performed, septoplasty is performed together.

People are rarely born with nasal septum perforation, and in most of cases, it is caused by acquired factors. It is known that it occurs most often after septoplasty or trauma, and the incidence rate after septoplasty is known to be 0.5% to 3.1% on average [1]. In addition, a nasal septum perforation can be caused by habitual use of nasal sprays, electrocauterization, infections such as tuberculosis, candida, and syphilis, heavy metals, and tumors. It is very important to prevent a nasal septum perforation as it increases the risk of causing a saddle nose and can cause various discomforts such as nasal obstruction, whistling, and crusting.

The most important thing to prevent a nasal septum perforation after septoplasty is to carefully dissecting the mucous membrane during surgery. However, if the nasal septum is very curved or the spur is large, it may inevitably damage the nasal septum mucosa. If a nasal septum perforation is expected due to mucosal damage during surgery, the use of autologous grafts such as nasal septum cartilage or bone plate, or inferior turbinate mucosal flap, or artificial grafts such as AlloDerm® (LifeCell, Branchburg, NJ, USA) or MegaDerm® (L&C BIO, Seoul, Korea) would prevent it. Alternatively, it is also useful to apply fibrous coagulant, suture the graft, or insert a silastic sheet for prevention [2-5]. This study was conducted to find out whether a procedure using a compressed autologous cartilage piece and a 0.254 mm silastic sheet would be effective in preventing a nasal septum perforation.

The analysis was conducted retrospectively based on the medical records of a total of 195 patients who underwent septoplasty for a deviated septum at the Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery at Dong-A University Hospital from January 2019 to December 2020. It covers preoperative symptoms, medical history, preoperative imaging tests, endoscopy, and postoperative complications. The procedure of this study was performed on 195 patients whose septal mucosa was in close proximity to each other during septoplasty and was damaged by at least the size of 1 cm.

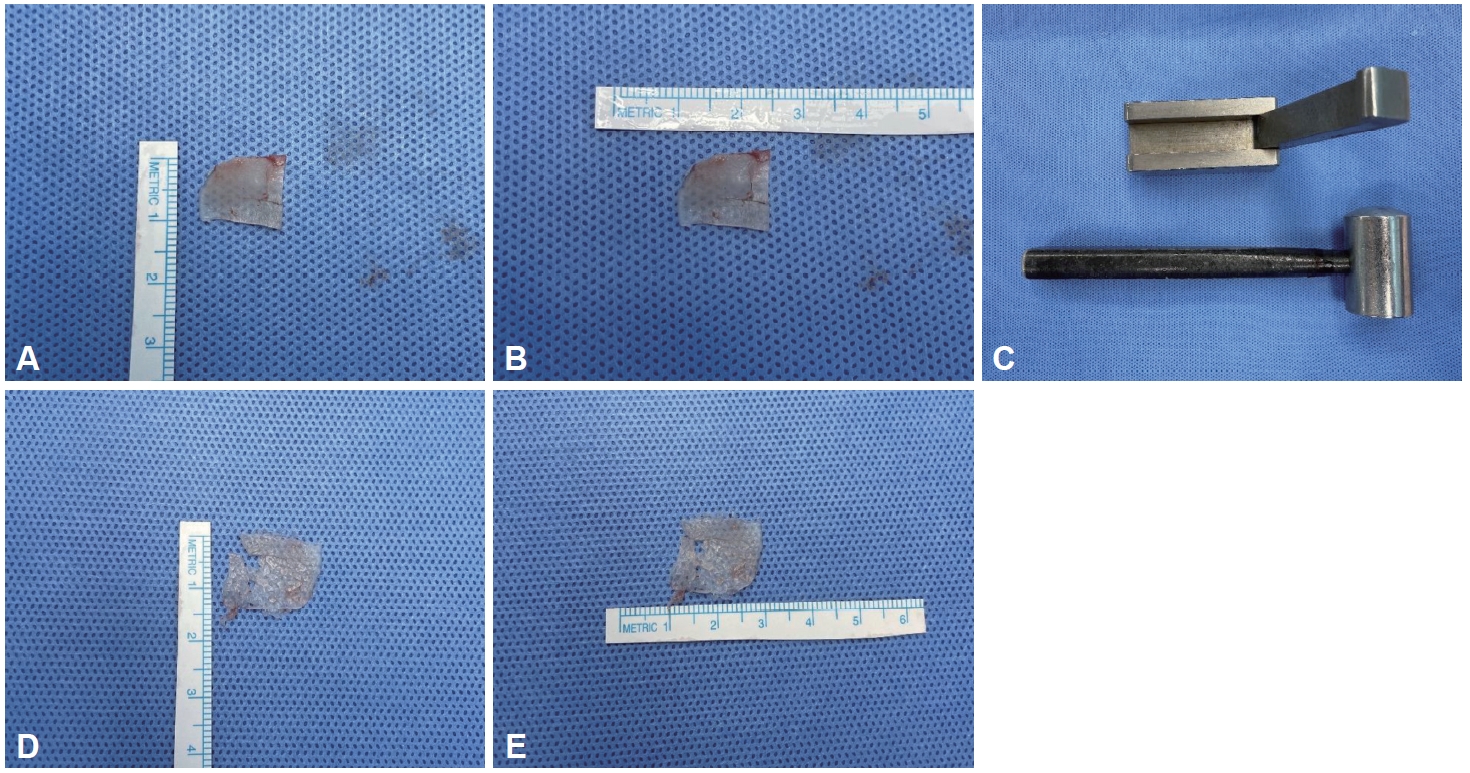

The operation was performed under general anesthesia and by a single operator (WY Bae). In all cases, septoplasty was performed in a conventional way. For the patients with concerned with nasal septum perforation after surgery, the procedure was performed in the following ways. First, the patient’s own cartilage was compressed using a cartilage crusher (Karl Storz Germany-523900; Karl Storz, Walsdorf, Germany) to make it thinner and wider (Fig. 1). It was then reinserted between the damaged mucosa. After inserting the cartilage, it was confirmed that the cartilage was in place with an endoscope. Then, a 0.254 mm thin silastic sheet (Non-Reinforced Sheeting, Bioflexus, Kingman, AZ, USA) was cut enough to cover the area concerned with perforation, and then the area was sutured (Fig. 2). After covering the thin silastic sheet (Non-Reinforced Sheeting, Bioflexus), a 1 mm thick silastic sheet (Internal Nasal Splint, MEDTRONIC, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was inserted from the front to the back of both septums, and then penetrably sutured on the anterior portion of the septum. After that, nasal packing with a non-absorbable packing material and Vaseline gauze was placed as a last step. The next day after surgery, the non-absorbable packing material and Vaseline gauze located inside the nose were removed. The 1 mm thick silastic sheet (Internal Nasal Splint, MEDTRONIC) was removed on the 5th day after surgery. Then, the thin silastic sheet (Non-Reinforced Sheeting, Bioflexus) was checked and removed after the mucous membrane was completely regenerated during follow-up at the outpatient clinic.

This study was conducted after being reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Dong-A University Hospital (approval number: DAUHIRB 19-149). The informed consents were waived because the study was conducted retrospectively based on medical records.

There was a total of 9 cases which included 7 male and 2 female patients (Table 1). Their average age was 52.8 years (26- 78 years), and the main complaint was mostly nasal obstruction. Out of all cases, only one had a previous history of Caldwell Luc’s operation or nasal bone closed reduction surgery. There were no malignant tumors, traumatic trauma to the nose, tuberculosis, or systemic diseases that could affect perforation such as syphilis, or a history of exposure to heavy metal toxic substances in all cases. Except for one case with an approach of extracorporeal septoplasty, the rest were approached with a hemitransfixision incision. All the patients had mucosal damage in the cartilaginous part of the nasal septum. Their thin silastic sheets (Non-Reinforced Sheeting, Bioflexus) were removed 3 weeks after surgery on average. The average followup period after surgery was 3 months (1-9 months).

In one case, perforation occurred in the cartilage portion of the nasal septum 2 months after surgery. In 8 other cases, no septal perforation was found during follow-up for more than 1 month, and the damaged nasal septum mucosa on both sides was well regenerated. For the case of nasal septum perforation, the patient did not complain of any particular symptom so that has been monitored without additional surgery or procedure (Fig. 3).

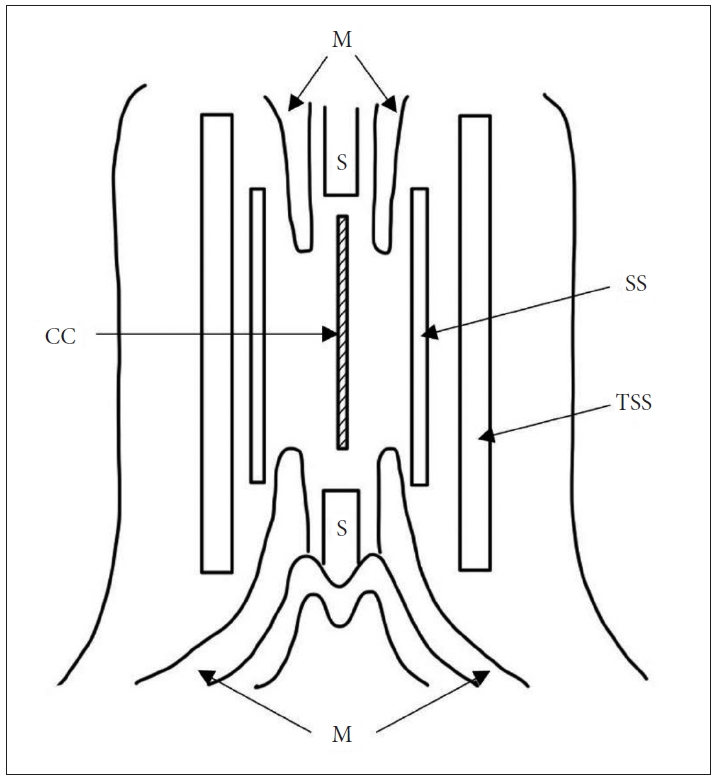

If perforation is expected during septoplasty, there are various methods to compensate. In general, bone tissue or cartilage tissue can be inserted between the mucous membranes. In addition, various techniques can be adopted depending on the operator’s experience such as inserting these tissues, suturing the mucosal tissue, inserting a silastic sheet, or applying a fibrin glue to the inserted tissue to fix it [3-5]. In this study, compressed cartilage pieces, thin silastic, and thick silastic sheets (Internal Nasal Splint, MEDTRONIC) were used (Fig. 4).

In these cases, the patient’s own cartilage collected during septoplasty was first stretched with a compressor and then inserted between the mucous membranes on both sides. The advantage is that there is no rejection reaction due to the use of the patient’s own cartilage. According to Breadon et al. [6], compressing the autologous cartilage fragments between the mucous membranes for transplantation stimulates the formation of new cartilage more compared to when they are simply inserted. In addition, the effect of the compressed cartilage fragments does not require a separate suture for engraftment with the surrounding tissue because the surface area becomes much wider and becomes sticky. According to Nolst Trenité et al. [7], when the cartilage is compressed and used, the flexibility of the cartilage increases which makes it easier to handle and reduces the overlapping part with the remaining bone and cartilage, so that the defect can be filled well. It has been demonstrated that the expected nasal septum perforation can be effectively prevented through animal experimentation.

Many people including Cakmak et al. [8] tested the degree of cartilage compression in six stages: intact, slightly crushed, moderately crushed, significantly crushed, severely crushed, and diced. It was confirmed that chondrocyte proliferation and bone metaplasia were observed when it was slightly crushed. However, Cakmak et al. [8] confirmed that chondrocyte proliferation and bone metaplasia did not occur, and the viability of the cartilage decreased when the cartilage was severely crushed and diced, which showed the need for an appropriate strength during compression. The 9 cases conducted all used cartilage all slightly to moderately crushed based on the above-mentioned classification.

One of the concerns when it comes to the use of compressed autologous cartilage during septoplasty is the possibility of resorption. Stoksted and Ladefoged [9] reported no resorption or infection after surgery using the compressed cartilage. In addition, there has been no change observed when Mutlu [10] kept compressed cartilage in saline for 2 years. When checked 2 years after transplantation for another surgery, the transplanted fragments were kept intact without being melted or absorbed [10].

The silastic sheet is an inert silicone rubber that is easy to obtain because it is relatively safe and inexpensive to use on the human body. Because it causes less adhesion between the operated area and the surrounding mucous membrane, it is used in various surgery [11-13]. This serves as a splint that prevents adhesion between the operated area and the surrounding mucous membrane in septoplasty, supports the septum weakened after correction, and induces natural regeneration [14,15]. Jung et al. [16] had studied the degree of mucosal regeneration and patient discomfort in a double-blind manner for 2 weeks after surgery based on whether or not a 0.3 mm thick silastic sheet was used during septoplasty and obtained significantly good results with the use of the sheet.

When performing septoplasty in Dong-A University Hospital, a 1 mm thick silastic sheet (Internal Nasal Splint, MEDTRONIC) is used in general. However, this cannot be used more than a week after surgery due to discomfort such as foreign body sensation and nasal obstruction. The 1 mm silastic sheet was removed 5 days after the operation. On the other hand, the 0.254 mm thin silastic sheet (Non-Reinforced Sheeting, Bioflexus) had much less discomfort for the patient and could be used for an average of 3 weeks after the operation, which prevented the adhesion between damaged mucous membrane and other areas.

In 8 out of 9 cases, the mucous membrane damage during septoplasty was completely regenerated. In addition, there was no autologous cartilage protrusion through the damaged area of the mucous membrane, no inflammatory reaction or other complications related to the silastic sheet. For one particular patient that had septal perforation, his age (78 years old) may have had a significant impact. When the thin silastic sheet (Non-Reinforced Sheeting, Bioflexus) was removed from him 3 weeks after surgery, the mucous membranes were all well regenerated which means the procedure was successful. However, after the sheet was removed, some damage occurred because of the weekend mucous membrane, and it didn’t recover due to the age.

With only 9 cases in total and a short follow-up period of 1 month in 3 cases, it is too limited to generalize the results. In addition, there is a limit to securing statistical significance as patient control studies have not been conducted in cases where this formula has not been implemented or other formulas have been conducted.

In conclusion, the authors believe that the procedure described in this study can be helpful in preventing postoperative perforation with the use of compressed cartilage and silastic sheet without the additional cost of using other implants to fill the post-operative septal defect.

Notes

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Woo Yong Bae. Data curation: Sang Jun Kim, Young Gun Kim. Formal analysis: Woo Yong Bae. Investigation: Young Gun Kim. Methodology: Woo Yong Bae. Project administration: Woo Yong Bae. Resources: Woo Yong Bae. Supervision: Sang Jun Kim. Validation: Woo Yong Bae. Visualization: Young Gun Kim. Writing—original draft: Sang Jun Kim, Young Gun Kim. Writing—review & editing: Sang Jun Kim, Young Gun Kim.

Fig. 1.

Cartilage crusher and cartilage crushing. A: Autologous cartilage before crushing (length: 1 cm). B: Autologous cartilage before crushing (width: 1.5 cm). C: Cartilage crusher (Karl Storz Germany-5239; Karl Storz, Walsdorf, Germany). D: Autologous cartilage after crushing (length: 1.5 cm). E: Autologous cartilage after crushing (width: 2 cm).

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative finding. A, B: Both septal mucosal was perforated. C: The crushed septal cartilage was inserted between the perforated mucosa. D, E: Thin silastic sheet (0.254 mm; Non-Reinforced Sheeting, Bioflexus, Kingman, AZ, USA) was covered on both perforated septal mucosa.

Fig. 3.

Representative case where both septal mucosa well healed. A: Right nasal cavity. B: Left nasal cavity.

Fig. 4.

Schematic diagram. S, septal cartilage; M, septal mucosa; CC, crushed cartilage; SS, silastic sheet (0.254 mm thickness; NonReinforced Sheeting, Bioflexus, Kingman, AZ, USA); TSS, thick silastic sheet (1 mm thickness; Internal Nasal Splint, MEDTRONIC, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Table 1.

Clinical data of patients with operation

References

1) Quinn JG, Bonaparte JP, Kilty SJ. Postoperative management in the prevention of complications after septoplasty: a systematic review. Laryngoscope 2013;123(6):1328-33.

2) Choi JS, Jin KH, Park MW, Kang SH, Lim DJ, Yu MS, et al. Prevention technique using inferior turbinate mucosal flap for septal perforation after septoplasty. J Rhinol 2014;21(1):37-40.

3) Yun DH, Kim YJ, Kim JH, Lee BJ. Causes and clinical characteristics of the nasal septal perforation. J Rhinol 2000;7(1):64-8.

5) Lee JY, Lee SW, Lee JD, Lee YM, Shin JM, Lee JY. Usefulness of autologous cartilage and fibrin glue for the prevention of septal perforation during septal surgery: a preliminary report. Korean J Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg 2006;49(6):611-5.

6) Breadon GE, Kern EB, Neel HB 3rd. Autografts of uncrushed and crushed bone and cartilage. Experimental observations and clinical implications. Arch Otolaryngol 1979;105(2):75-80.

7) Nolst Trenité GJ, Verwoerd CD, Verwoerd-Verhoef HL. Reimplantation of autologous septal cartilage in the growing nasal septum. II. The influence of reimplantation of rotated or crushed autologous septal cartilage on nasal growth: an experimental study in growing rabbits. Rhinology 1988;26(1):25-32.

8) Cakmak O, Bircan S, Buyuklu F, Tuncer I, Dal T, Ozluoglu LN. Viability of crushed and diced cartilage grafts: a study in rabbits. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2005;7(1):21-6.

9) Stoksted P, Ladefoged C. Crushed cartilage in nasal reconstruction. J Laryngol Otol 1986;100(8):897-906.

10) Mutlu V. A novel surgical technique: crushed septal cartilage graft application in endonasal septoplasty. Auris Nasus Larynx 2019;46(2):218-22.

11) Tanabe M, Takahashi H, Honjo I, Hasebe S, Sudo M. Factors affecting recovery of mastoid aeration after ear surgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 1999;256(5):220-3.

12) Hwang K, Kita Y. Alloplastic template fixation of blow-out fracture. J Craniofac Surg 2002;13(4):510-2.

13) Schmidt BL, Lee C, Young DM, O’Brien J. Intraorbital squamous epithelial cyst: an unusual complication of Silastic implantation. J Craniofac Surg 1998 9(5):452-5. discussion 456-8.

14) Alaani A, Jassar P, Smith I. The use of silastic nasal splints in the treatment of chronic epistaxis and nasal septal ulceration. Ear Nose Throat J 2006;85(11):738-9.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print